The guiding light of Italian politics has suggested he does not intend to run for a second seven-year mandate. He also cited an unheeded predecessor with some ideas as to how the Constitution should be changed. Will this shuffle the cards in the ongoing government crisis?

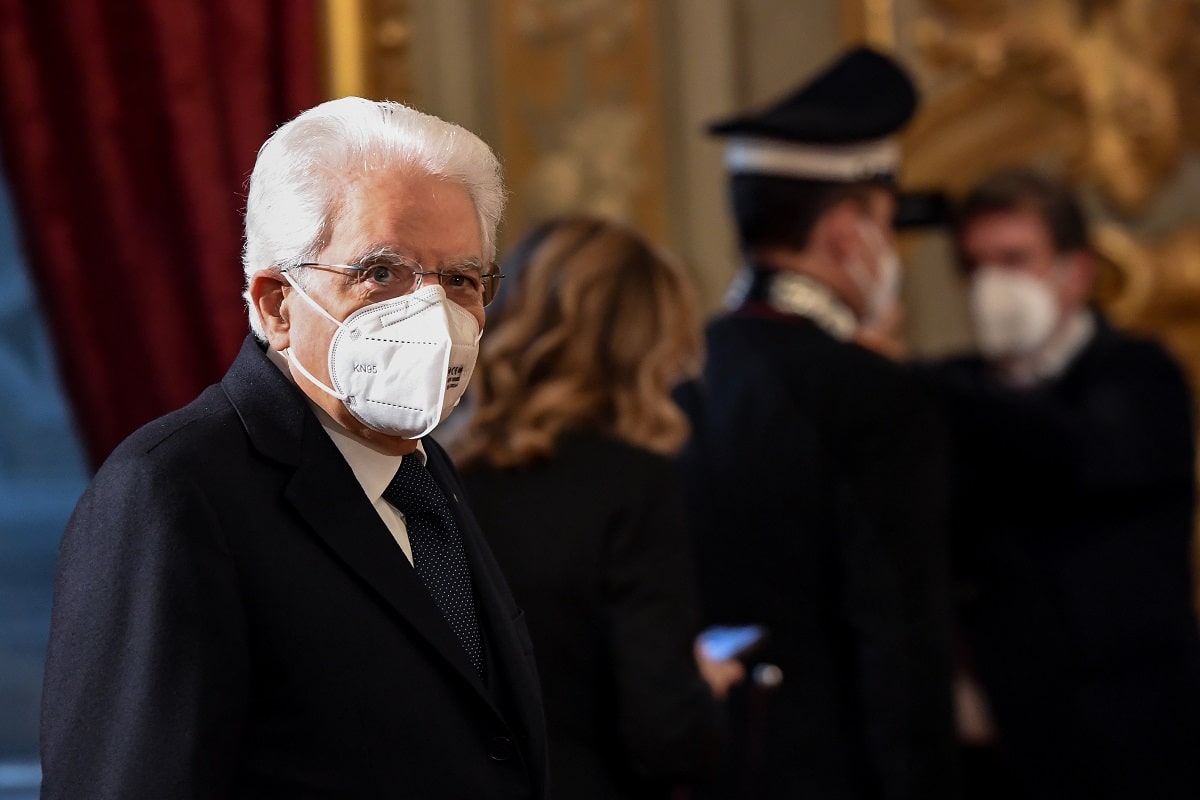

At this time, President Sergio Mattarella is perceived as the most authoritative leader in the landscape of Italian politics. His steadfast impartiality has earned him the respect of politicians from across the aisles, as well as the general public’s.

In the ongoing government crisis he represents the stability that the country so desperately needs, that which has been lacking in the last two governments under his watch. He does not speak often, but when he does, Italians listen. And on Tuesday he held a speech charged with meaning for the country.

The current crisis – and the parties’ tactical calculations – hinge on a few key dates. Mr Mattarella’s mandate ends in January 2022, and whichever political force will build the next government will also have the chance to name his successor.

More still, the Italian Constitution prohibits governmental elections in the six months that precede the President’s election (the so-called “white semester”). This measure, as well as another constitutional article barring the President from dissolving Parliament in the last months of his mandate, were intended to avoid last-minute scrambling and sly manoeuvres among institutional powers.

Mr Mattarella, a constitutionalist by trade, said that he does not wish to run for a second mandate. He also made a point of citing Antonio Segni, the fourth President of the Italian Republic, on the 130th anniversary of his birth.

The President’s speech detailed his predecessor’s unheeded suggestion, dating back to 1963, to grant the President one term only, deeming “seven years enough to grant the continuity of the State’s action.” That way, the suspect that the President would wield his power to be re-elected would be rooted out.

Consequently, the clause barring the President from dissolving Parliament can also be rescinded. This, for all intents and purposes, was a call to improve the balance and resilience of the Italian political system.

These words have heavy implications on the here-and-now. Part of the political games being played among parties to form the next government is aimed at obtaining the power to elect the next president. In his speech, Mr Mattarella noted that the very power to do so can “alter” the checks and balances of the State, especially in a difficult moment – such as the current one.

The overarching call coming from the President was one of political responsibility, one he chose to demonstrate in practice and good faith. One could argue he is inviting the current political forces to look beyond lowly political games and focus on the actual welfare of the country. It wouldn’t be the first time that he does that – with good reasons.

Caught between the ongoing pandemic and the economic downfall, many Italians are amazed – and angry – at the show being put on by their MPs. In the past weeks, they have seen politicians switching sides time and again, attempts to form weak governments out of spite of other forces, and what they see as inane, cynical games at their expense.

Some within the current governing coalition were hoping to hold onto Mr Mattarella, Italy’s firm hand on the rudder, and elect him a second time – a reasoning not devoid of a certain personal advantage. This is the exact behaviour that the President took pains to condemn.